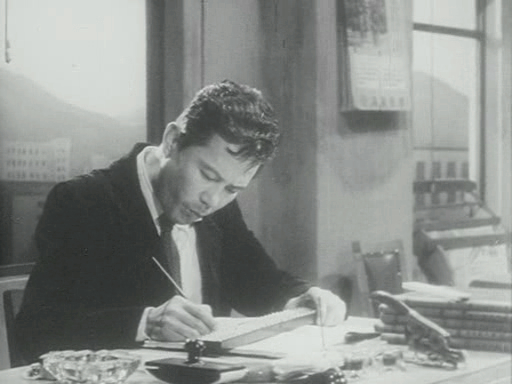

매년 여름 한국영화에 대한 강의를 한다. 초반부는 한국영화사에 집중되어 있어서, 학생들에게 여러 영화를 발췌해 보여주곤 한다. ‘미몽(1936)’, ‘반도의 봄(1941)’, ‘자유부인(1956)’, ‘지옥화(1958)’, ‘오발탄(1961)’, ‘마부(1961)’, ‘맨발의 청춘(1964)’, ‘휴일(1968)’, ‘바보들의 행진(1975)’, ‘야행(1978)’, ‘칠수와 만수(1988)’ 등을 보며 나는 몇 주 동안 서울의 변화를 목격한다.

한국전쟁 이전의 모습을 훑어보는 것으로 시작해서, 1950년대와 1960년대 초반 재래시장과 혼돈스런 재건을, 60년대 말의 점진적 도시화를, 1970년대엔 활보하는 행인들 위로 높이 올라간 빌딩의 모습들을 보게 된다(어떤 이유에선지 1970년대부터의 모든 한국영화에선 행인들이 지나가는 모습을 위에서 찍는 경우가 많은 것 같다). 1980년대 말이 되면 도시 전경에 부의 징후가 명확하게 나타난다. ‘칠수와 만수’ 끝부분에 고속터미널과 압구정 아파트단지의 상징적인 ‘헬리콥터샷’엔 달콤쌉쌀하고 잊을 수 없는 무엇인가가 있다.

지난 수 년간 서울의 이 같은 영화장면들이 내 기억 속에 쌓여왔다. 그럼에도 불구하고 도시는 수십 년간 너무 많이 변해서 대부분의 이미지가 마치 다른 공간에서 온 것처럼 느껴진다. 내가 버스를 타고 다니며 경험하는 서울과 아무런 접점이 없는 것 같다.

도시는 역사와 특별한 관계를 가진다. 그러나 어떤 도시들의 역사는 다른 곳보다 눈에 띈다. 또 어떤 도시에서는 풍경에서 역사를 읽을 수도 있다. 옛 것과 새 것의 충돌도 느낄 수 있다. 다양한 시대의 감각이, 대화(아마도 논쟁)를 해가며, 같은 공간에 옹기종기 모여있는 느낌이랄까? 주목을 받기 위해 옛 것과 새 것이 경쟁하는 지저분한 도시를 나는 항상 더 좋아했다. 그 곳은 눈에 띄게 아름답지만 과거가 주의 깊게 보존된 곳이다.

어떤 의미에서, 서울의 역사는 표면적으론 눈에 띈다. 경복궁 같은 고궁이나 숭례문 같은 랜드마크는 관광객과 내국인이 똑같이 방문하는 곳이다. 비록 도시의 다른 부분과 담을 쌓아 보존하고 있지만, 그 안에 들어가 지난 세기의 삶을 느낄 수 있다.

그러나 비극적이게도, 서울은 더 작지만 소중한 역사의 자투리를 잃었다. 이유는 명확하다. 도시의 대부분이 한국전쟁으로 파괴됐고, 전후의 불안한 상황은 재건이라는 것이 혼돈스럽고 일시적이었음을 의미했다. 도시 계획과 보존이, 힘겹게 살아가는 보통사람들의 근심과 왜 동떨어져 있었는지는 ‘오발탄’ ‘마부’ 같은 영화만 봐도 이해할 수 있다.

거대한 역사적 공간보다 더욱 그렇지만, 도시의 성격에 가장 큰 기여를 하는 건 역사의 작은 현상들이다. 물론 한옥, 왕릉, 사찰, 성벽 등 역사의 어떤 조각들은 서울에 남아있다. 더 새로운 발전 역시 도시 역사를 반영하도록 설계된다. 그러나 전쟁의 폐허에서 탈출한 서울의 엇갈린 역사를 생각해보라. 오늘날의 모습은 얼마나 다른가? 도시의 전경에서 얼마나 많은 서울의 역사를 읽을 수 있는가? 옛 것과 새 것의 충돌은 공평하지 못한 대회처럼 느껴지진 않는가? 오래된 한국영화를 보는 것, 그리고 서울의 잃어버린 이미지를 보는 것은 내게 그런 질문을 던진다.

배우 겸 영화칼럼니스트

<원문보기>

Seoul’s Lost History

Each summer I teach a class on Korean cinema. The first half of the class is devoted to Korean film history, and as I screen short excerpts of films for my students Sweet Dream (미몽, 1936), Spring of the Korean Peninsula (반도의 봄, 1941), Madame Freedom (자유부인, 1956), A Flower in Hell (지옥화, 1958), Obaltan (오발탄, 1961), The Coachman (마부, 1961), Barefoot Youth (맨발의 청춘, 1964), A Day Off (휴일, 1968), March of Fools (바보들의 행진, 1975), Night Journey (야행, 1978), Chilsu and Mansu (칠수와 만수, 1988) over several weeks I witness the transformation of Seoul.

After beginning with some brief glimpses of the city in the years before the destruction of the Korean War, we see the outdoor markets and chaotic reconstruction of the 1950s and early 1960s, the slow urbanization of the late 1960s, and then the appearance of high rise buildings and overhead pedestrian crossings in the 1970s. (For some reason, every Korean film from the 1970s seems to prominently feature an overhead pedestrian crossing.) By the late 1980s, manifestations of wealth appear more obviously in the cityscape. There’s something unforgettable and bittersweet about the iconic helicopter shots of the Express Bus Terminal and Apgujeong Apartments at the end of Chilsu and Mansu.

Over the years, many of these cinematic glimpses of Seoul have become lodged in my memory. And yet, the city has changed so much over the decades that most of the images feel like they come from a different place. They seem to have no connection to the Seoul I experience when I take the bus downtown.

Cities have a special relationship to history. But some cities’ histories are more visible than others. In some cities, you can read history in the landscape. You can feel the collision of the old and the new; a sense of diverse eras huddled together in the same cramped space, carrying on a conversation (or perhaps, an argument). I’ve always preferred messier cities where the old and the new compete for attention, over strikingly beautiful but carefully preserved places that feel frozen in the past.

In one sense, Seoul’s history is visible on the surface. Palaces like Gyeongbokgung and landmarks like Sungnyemun can be visited by tourists and locals alike. They often remain separate, walled off from the rest of the city, but you can step inside them and get a feel for life in past centuries.

But tragically, Seoul has lost much of the smaller, more everyday remnants of its history. The reason is obvious: much of the city was destroyed in the Korean War, and the unstable situation after the war meant that rebuilding was chaotic and temporary. One need only watch films like Obaltan and The Coachman to understand why city planning and preservation was far from the concerns of ordinary people struggling to get by.

More so than the large historical sites, it’s the small manifestations of history that contribute the most to a city’s personality. Of course, some bits of history do live on in Seoul hanok houses, royal tombs, Buddhist temples, the old city wall, etc. Some newer developments are also designed to reflect the city’s history. But imagine an alternate history, in which Seoul escaped the destruction of the war. How much different would the city look today? How much of Seoul’s history would we be able to read in its cityscape? Would the clash between the old and the new not feel like such an uneven contest? Watching old Korean films, and seeing these lost images of Seoul bring such questions to my mind.

달시 파켓 '대한민국에서 사는 법' ▶ 시리즈 모아보기

기사 URL이 복사되었습니다.

댓글0